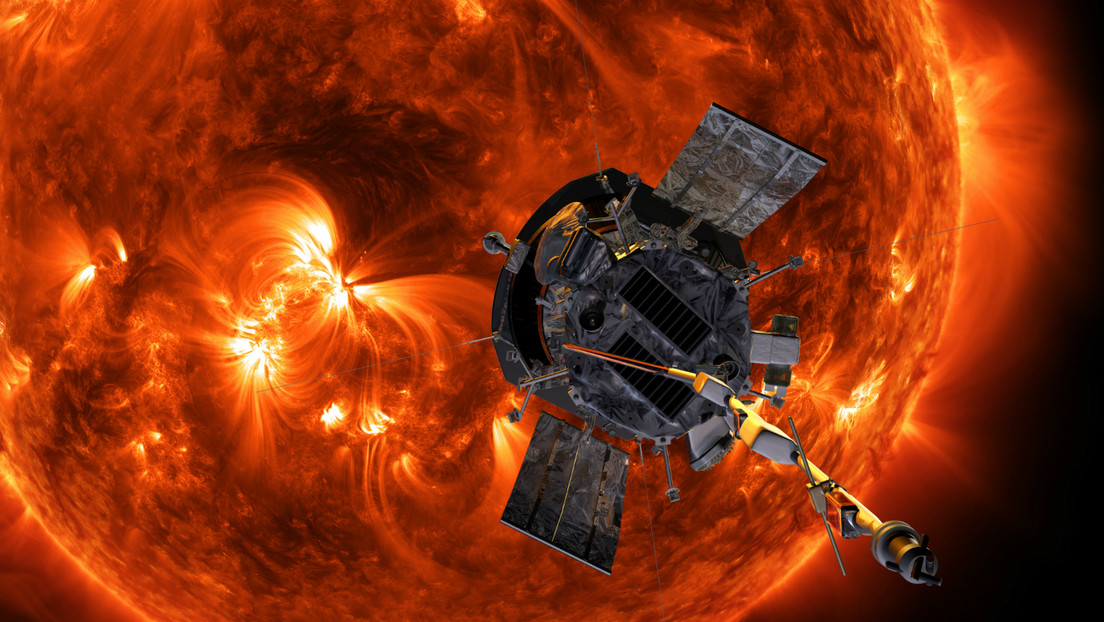

For the first time in the history of astronautics, a space probe has "touched" the Sun. The Parker Solar Probe has flown through the upper atmosphere of our star and has taken samples of particles and magnetic fields, NASA reported Tuesday in a statement.

For the first time in the history of astronautics, a space probe has "touched" the Sun. The Parker Solar Probe has flown through the upper atmosphere of our star and has taken samples of particles and magnetic fields, NASA reported Tuesday in a statement.

The agency noted that it is a new milestone and a great leap in solar science, comparing the achievement with the arrival of man on the Moon. The researchers hope that touching the matter the Sun is made of will help them uncover critical information about this star and its influence on the solar system.

"For the Parker Solar Probe to 'touch the Sun' is a monumental moment for solar science and a truly remarkable feat," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "This milestone not only provides us with deeper insights into the evolution of our Sun and its impacts on our solar system, but everything we learn about our own star also teaches us more about the stars in the rest of the universe."

The Parker Solar Probe solar probe was launched to study the Sun in 2018. It had to approach the Sun for seven years to reach its maximum distance, 6 million kilometers. The strategy is to get in and out quickly, taking measurements of the solar environment with an array of instruments deployed behind a thick heat shield.

On April 28 of this year, Parker crossed what is called the Alfvén critical limit for the first time. This is the outer edge of the crown. It is the point at which the solar material that is normally attached to the Sun by gravity and magnetic forces, is released to go out into space. The probe found the boundary about 13 million kilometers above the visible surface, or photosphere, of the Sun.

During the flyby, Parker Solar Probe entered and exited the crown several times. Finding out where these bulges align with solar activity coming from the surface can help scientists understand how events on the Sun affect the atmosphere and the solar wind. (Text and photos: RT)