By Jorge Wejebe Cobo/ACN

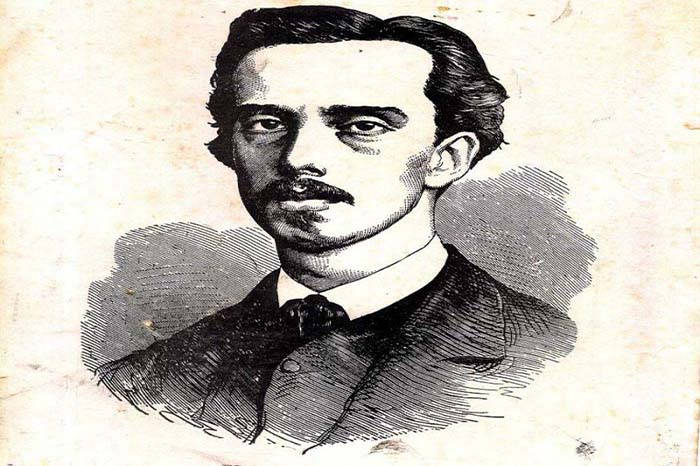

Ignacio Agramonte Loynaz saw the light of day for the first time in a stately town on December 23, 1841, 182 years ago, during a Christmas that seemed to predict a happy and peaceful existence for him in Santa María del Puerto del Príncipe (current Camagüey), but that newborn He would have a very different destiny when years later he decided to dedicate himself to the independence of his country by wearing the star that illuminates and kills.

His mother was María Filomena Loynaz y Caballero, heiress to a significant fortune, and his father Ignacio Agramonte Sánchez Pereira belonged to a family of lawyers linked to the most important wealth in the region.

After a few years, the city of Ignacio's childhood was shaken in 1851 when the patriot Joaquín de Agüero, a well-known and loved figure in the region for his social and cultural initiatives, took up arms against the metropolis and was apprehended, tried and publicly shot along with three other insurgents.

The shock at the crime against Agüero and his companions caused patriotic women to cut their hair and men to dress in black, in protest of the execution. The sacrifice of those martyrs penetrated very deeply into the independence ideas that would lead to the cry for independence of 1868, to which the people of Camagüey would join.

With the passage of time, the legend was woven of Agramonte's presence at the place of the torture, where he dipped a handkerchief in the patriot's blood and swore to avenge him, a fact very unlikely due to the siege that the colonial forces placed on access to the area. and above all forbidden for a child of just 10 years old.

But surely Agüero's example must have had a strong influence on the Agramonte and Loynaz family, not at all related to Spain, and on the child who was trained in applying himself to study and who as a teenager practiced fencing, horse riding and shooting in hunts in the extensive plains, which would prepare him physically and mentally.

His parents, ensuring that he had a complete education, sent him to Barcelona where he completed his secondary education and returned to enter the then pontifical University of Havana, from which he graduated in 1867 as a Doctor of Laws.

The young man seriously jeopardized his future as a lawyer in the defense of his thesis, in which he denounced the evils of the colonial regime and the right of Cubans to their own government, to which center authorities said that if they knew its contents with previously they would not have allowed Agramonte to graduate.

Thus, that lawyer returned to his homeland and on August 1st, 1868, he married the love of his life, Amalia Simoni Argilagos, who in addition to sharing his ancestry also coincided with the independence ideals and conspiratorial activities alongside the patriots of Camagüey who rose up on November 4, 1868, in the passage of the Las Clavellinas river, 13 kilometers from Puerto Príncipe.

Ignacio Agramonte was not in Las Clavellinas because he was carrying out conspiratorial tasks in the city, but on November 11 he rose up at the El Oriente sugar mill, near Sibanicú.

The story goes that he attended the meeting with the Homeland dressed in a red striped shirt, one of the first gifts from his wife Amalia, who would accompany him to the jungle until she was detained by the Spanish and deported.

The uprising in Camagüey forced the Spanish command to redefine its strategy aimed at quelling the insurrection in the eastern zone, counting on the rest of the Island as a safe rearguard and provider of the necessary economic resources coming mainly from the sugar industry.

In a short time, the young lawyer stood out for his great combative capacity, and for his radicalism and political thinking, he would be a fundamental figure for the consolidation of the first libertarian feat that began on October 10, 1868, with which the hundred years of struggle of the Cuban people to achieve their true national independence.

The hero opposed the surrender and proclaimed in the defining moments "end once and for all the lobbying, the demands that humiliate, Cuba has no other way than to achieve its redemption, wresting it from Spain with force of arms."

He had contradictions with President Carlos Manuel de Céspedes due to disagreements in the ways of directing the struggle, however this did not break the unity of the independence ranks, nor did it show any ambition for power. And so as not to leave any doubts, he responded to the comments of his subordinates by stating bluntly: “I will never allow the President of the Republic to be gossiped about in my presence!”

El Mayor, the nickname by which he is called, fell in combat on May 11, 1873 in the Potreros de Jimaguayú. He was only 31 years old at the time and, thanks to courage, audacity and great talent as a strategist and military organizer, he had established himself as one of the main leaders of the Ten Years' War and deserved a place in immortality in national history.

José Martí in his article “Céspedes and Agramonte” made the definitive judgment on these two leading figures of our deeds for independence when he said: “From Céspedes the impetus, and from Agramonte the virtue (…). The one challenges with kingly authority; and with strength as of light, the other wins. He will come history, with his passions and justices; and when he has bitten them and trimmed them to his liking, he will still remain in the beginning of the one and in the dignity of the other, a matter for the epic. (Photo: ACN/Archive)