Havana, Nov. 5 - On October 14, 1975, apartheid South Africa invaded Angola from usurped Namibia, with the knowledge and approval of the United States government.

The aggression aimed to prevent the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA, for its acronym in Spanish) from declaring the independence of Portugal's richest colony in Africa and forming a government that would legitimately represent the Angolan people.

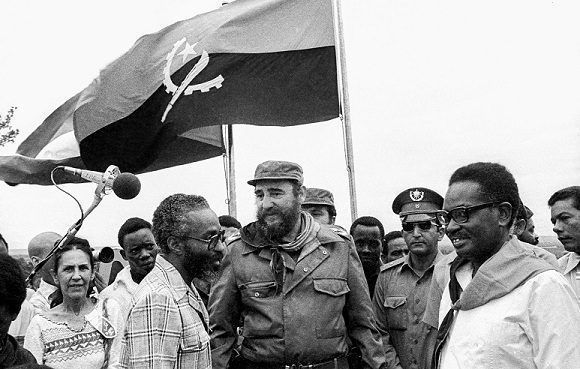

Pretoria was aware of Agostinho Neto's firm opposition to the apartheid regime and his deep commitment to the struggles of Namibian, Zimbabwean, and South African patriots. Therefore, it bet on aligning with Washington to achieve the American objective of installing a puppet government in Luanda, headed by Jonas Savimbi or Holden Roberto.

By then, the Gerald Ford administration had approved the covert operation IAFEATURE to provide advisors, weapons, and money to Savimbi's UNITA gangs, Roberto's FNLA, as well as the army of the dictator Mobutu of what was then Zaire. However, in the ensuing civil war unleashed in Angola against the MPLA, the movement led by Neto emerged victorious.

Thus, it proceeded to declare Angola's independence on November 11, 1975, the date set for this purpose in the Alvor Agreement, signed on January 15 of that year.

Faced with the failure of UNITA and the FLNA to carry out their orders, Washington and the CIA looked to racist South Africa. The Americans were concerned that the presence of several hundred Cuban military instructors would strengthen the training of the People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA, for its acronym in Spanish), the armed wing of the MPLA.

South Africa invaded Angola with over a thousand men, armored vehicles, and artillery. In the initial days, the Zulu column advanced relentlessly northward, breaking through the flimsy defenses of the inexperienced FAPLA.

Emboldened by the direct support of the South African Defence Force (SADF), the gangs of Savimbi and Roberto advanced towards Luanda from the south and north, respectively. In the White House, it was estimated that the Soviet Union would not come to the aid of Neto and the MPLA due to Moscow's fear of jeopardizing its policy of détente with the United States.

In their equation, they did not include the strategic vision and determination of Fidel and the internationalist vocation of a small country located 11,000 kilometers away from Angola.

Up to the moment of the racist invasion, the Commander in Chief of the Cuban Revolution had acted with restraint regarding the scale of military aid provided to the MPLA, following Neto's request, due to the refusal of Brezhnev, the then Soviet leader, to support sending Cuban combat troops to Angola.

Fidel had accurately assessed the threat that foreign assistance to the UNITA-FNLA alliance represented for the independence of an MPLA-governed Angola and for the very lives of the Cuban military advisors who were there.

This perception was reinforced by reports sent from Luanda by Commander Raúl Díaz-Argüelles, the head of the then recently created Cuban Military Mission in Angola, who even urged sending reinforcements in the face of an imminent large-scale South African intervention, supported by the United States.

Events proved them right. On October 14, South Africa invaded from Namibia.

In its rapid march toward Luanda, the Zulu column encountered only real resistance on November 2nd and 3rd, in Catengue, in Benguela province, offered by several dozen Cuban instructors and their Angolan pupils. The internationalists suffered four dead, seven wounded, and 13 missing.

News of the sacrifice of the Cuban military advisors reached Havana on November 4th. It was then that Fidel Castro and the revolutionary government confirmed that the South African racists had invaded.

At dawn on the 5th, Fidel and the top Cuban leadership decided to urgently send troops to thwart the plans of the United States and South Africa to seize Angola, and not to abandon to their fate the instructors who were already fighting and dying in fulfillment of that mission.

It was a momentous, fully sovereign decision, despite the expressed Soviet opposition to dispatching Cuban troops to Angola. CIA analysts were stunned: they never could have imagined that Cuba would act with such determination, more typical of a military power than a small, underdeveloped, and economically blockaded nation.

The Island acted on its own accord, faithful to its revolutionary values and ethical attitudes, and in accordance with the thinking of Fidel and Che Guevara to collaborate with the peoples of Africa who were fighting against colonialism and racism.

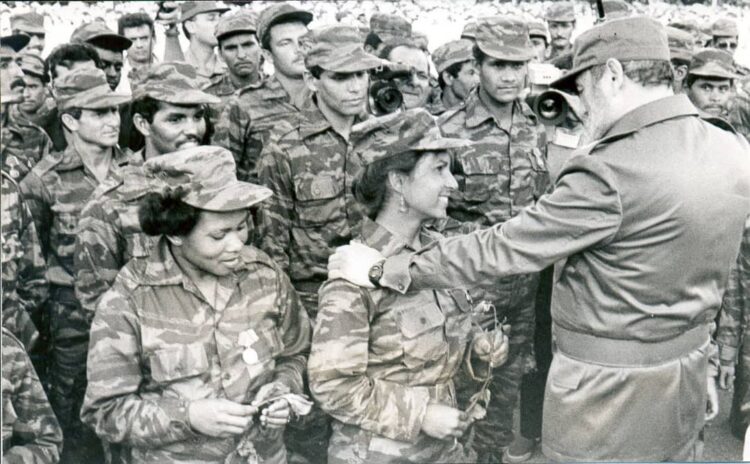

The first units mobilized were the Ministry of the Interior's Special Troops Battalion and a land artillery regiment. The former would travel in four-engine turbo-prop Bristol Britannia aircraft from Cubana de Aviación, and the latter would follow by sea.

Before their departure, Fidel spoke with the 158 combatants of the first company of the MININT battalion. He spoke to them about the imperative need for the operation, that several Cubans had died, and that it was essential to stop the South African racists before they reached Luanda.

The harsh reality for the 652 men of the special troops battalion was that once they arrived in Angola, there was no way to evacuate them. None of the combatants refused to depart for a battlefield located on the other side of the world.

Two Britannias took off from Havana for Angola carrying on board, dressed in civilian clothes, the combatants of the first company of the special troops. Operation Carlota began, 50 years ago. (Text and photos: Trabajadores Digital)