France, Feb 24 - Why did humans start talking? Scientists suggest that genetics played an important role and say that the evolution of this unique ability was key to our survival.

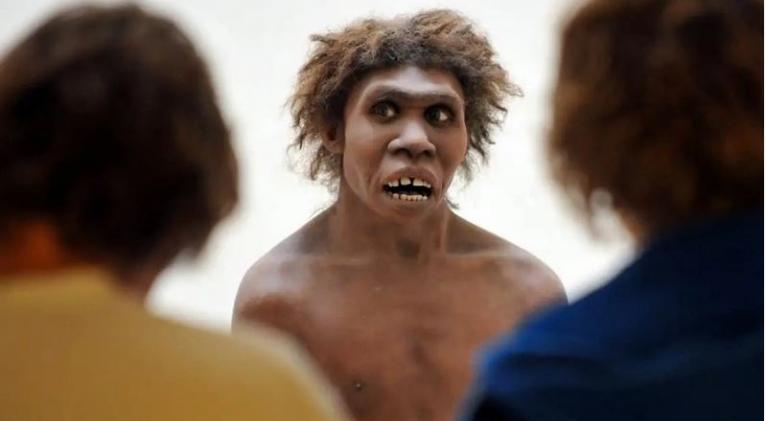

A new study links a particular gene to the ancient origins of spoken language and proposes that a protein variant found only in humans may have helped us communicate in a novel way. Speech allowed us to share information, coordinate activities and transmit knowledge, giving us an advantage over extinct relatives such as Neanderthals and Denisovans.

The new work is "a good first step to start investigating the specific genes" that may affect speech and language development, said Liza Finestack of the University of Minnesota, who was not involved in the research.

What scientists learn could even one day help people with speech problems.

The genetic variant studied by the researchers was one of a variety of genes “that contributed to the emergence of Homo sapiens as the dominant species we are today,” said Dr. Robert Darnell, one of the authors of the study published in the journal Nature Communications.

Darnell has studied since the early 1990s the protein called Nova1, known to be crucial for brain development. For the latest research, scientists in his lab at Rockefeller University in New York used Crispr gene editing to replace the Nova1 protein found in mice with the uniquely human type to test the real effect of the genetic variant. To their surprise, this changed the way the animals vocalized when they called to each other.

Baby mice with the human variant of the protein squealed differently than their normal littermates when their mother approached. Adult male mice with the variant muttered differently than others when they saw a female in heat.

Both are scenarios where mice are motivated to communicate, Darnell said, "and they spoke differently" to the human variant, illustrating its role in speech.

Shared Variant

This isn't the first time a gene has been linked to speech. In 2001, British scientists claimed to have discovered the first gene related to a language and speech disorder.

Called FOXP2, it became known as the human language gene. But while it is involved in speech, it turned out that the variant in modern humans was not exclusive to us. Later research found that it was shared with Neanderthals. The Nova1 variant in modern humans, on the other hand, is exclusively in our species, Darnell pointed out.

The presence of a genetic variant is not the only reason why people can speak. This ability also depends on factors such as the anatomical characteristics of the human throat and the areas of the brain that work together to allow people to speak and understand language.

Darnell hopes that this recent work will not only help people better understand their origins, but also lead to new ways to treat speech-related problems.

Finestack of the University of Minnesota indicated that genetic findings are more likely to one day allow scientists to detect, at a very early stage in life, who might need speech and language therapies. (Text and Photo: Cubasí)