A group of researchers have discovered the oldest heart known to science. The finding occurred in the remains of a fish with jaw 380 million years ago which, together with its fossilized stomach, intestine and liver, sheds light on the evolution even of human bodies.

A group of researchers have discovered the oldest heart known to science. The finding occurred in the remains of a fish with jaw 380 million years ago which, together with its fossilized stomach, intestine and liver, sheds light on the evolution even of human bodies.

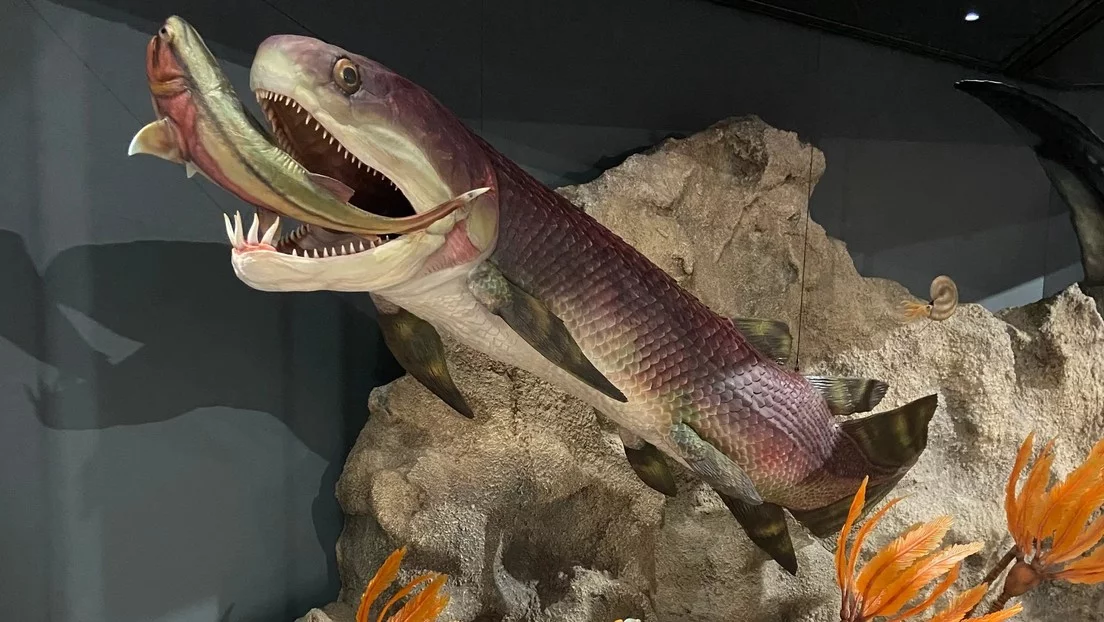

The discovery occurred in the Gogo Formation in northwestern Australia, in an extinct class of armored fish, the arthrodiers, who swam between 419 and 358 million years ago and who, despite their ancient origins, has shown that the anatomy of his body was not so different from that of modern sharks.

"Evolution is often thought of as a series of small steps, but these ancient fossils suggest that there was a larger jump between jawless and jawed vertebrates," study lead researcher Kate Trinajstic, of the Curtin School of Molecular and Life Sciences and the Western Australian Museum. "These fish literally have their hearts in their mouths and under their gills, just like sharks today," she added.

In the article published this week in the journal Science, the scientists found that the position of the organs on the body of this specimen is similar to the modern anatomy of sharks.

In addition, they presented a 3D model of the complex S-shaped heart of the arthrodire, which consists of two chambers, where the smaller one sits on top of the larger one. Such features, experts say, developed in these early vertebrates, offering a unique window into how the head and neck region evolved to accommodate jaws, a key stage in the evolution of our own bodies.

"For the first time, we can see all the organs together in a primitive jawed fish, and we were especially surprised to learn that they weren't that different from us," Trinajstic said. "However, there was a critical difference: The liver was large and allowed the fish to remain buoyant, like sharks today," he added.

For the study, the researchers used beams of neutrons and synchrotron X-rays to scan the samples, still embedded in limestone. They then reconstructed the images of the soft tissues inside them based on the different densities of minerals deposited by the bacteria and the surrounding rock.

This discovery along with previous muscle and embryo findings makes Gogo's arthrodires the best understood jawed stem vertebrates and clarifies an evolutionary transition in the line to living jawed vertebrates, including mammals and humans. (Text and photo: RT in Spanish)