Havana, Feb 6. - International meetings often bring surprises. At one of them, some time ago, I met an old classmate from Kiev University. Yes, I studied philosophy and lived in Soviet Ukraine for five years. My classmate was a diligent, intelligent student, and he easily learned Spanish from the Cubans. He was not a member of the CPSU, but the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the capitalist direction taken by its former republics led him to join one of the communist parties that emerged later. Since then he has been an active defender of the Cuban Revolution.

We have since met more than once, in Havana and Caracas, the two centers of the Latin American revolution. But when we talk, the philosophical categories planted by Lenin seem to float without nourishing roots in the conversation: not all the statements or positions heard in flight can be defined as idealist or materialist without more (sometimes, it is not even what matters), nor are all those who defend conservative positions, are well-off bourgeois or proto-bourgeois clinging to material interests.

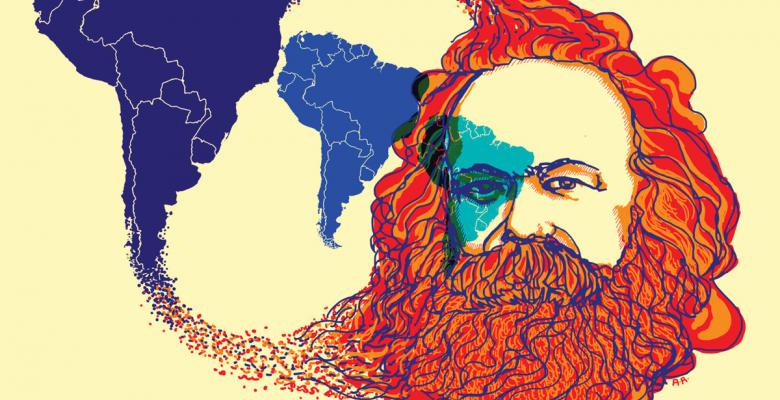

The cultural war kidnaps the unwary, the unprepared; sometimes it even drowns those who know how to swim best. Today's world is as complex as yesterday's, perhaps as it always was, but it changes more quickly. And Marxist philosophy runs after events, barely managing to catch up with them. It will not do so from the old cabinet; nor, however modern it may seem (the word modern already seems out of date to me), from the infinite world of the Internet and its networks.

The most important philosophical problem remains how to transform the world, and contrary to what seems inevitable, how to circumvent the form, to make the content prevail. New technologies, which are no longer the ones that prevailed just five years ago, bury us in inaction. And they fill our minds with unnecessary or false data and hypotheses that shine like neon lights. That is, attractive and easy to consume, but ephemeral and misleading. The truth, before, now and later, is in the street, with the people, it is what instructs, prepares and defends the people.

“Positivist” Marxism—useless and essentially reformist—is not only the manualistic and simplifying Marxism of the Soviet era; it is also the paralyzing one that, protected by the data of reality, and in the security of “two plus two equals four,” is satisfied with “the possible,” pretends to go far and stays close, promises profound changes and remains on the edge. Being a Marxist, I insist, it is not knowing every word, every text of Marx or Lenin, or any other later thinker; it is knowing how to use this theoretical and practical instrument to transform the world in favor of the humble. It is being a revolutionary.

José Martí, who was a voracious reader, and an insatiable connoisseur of all the avant-garde theories of his time, wrote: “It is the human torment that to see well one needs to be wise, and forget that one is wise.” The solution to the war between NATO and Russia will not be —as my friend would have wished, as Lenin understood possible in other historical circumstances for Tsarist Russia involved in the First World War— the socialist revolution in the contending countries. Not conforming with what is possible does not mean ignoring it; it is about never losing sight of the horizon, contemplating the scenario from above, because looking at ground level does not allow one to identify the paths or to know who are friends and enemies.

It has been more than forty years since I set foot on Ukrainian soil, since I have seen the majestic red building that housed the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Kiev, and since I have not shuffled my feet among the dry, yellow and red leaves that carpet Taras Shevchenko Park in autumn. In its classrooms studied young people from all the Soviet republics, from Eastern Europe, but also from Spain, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Latin America and Africa.

The brotherhood of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples seemed to be enshrined in the monument to Bogdán Jmelnitski, the Ukrainian Cossack who sealed a pact of unity with Tsar Alejo I of Russia in 1654. My friend, born in Kiev, does not consider himself Ukrainian or Russian. When I ask him, he answers: “I am Soviet.”

But I want to remember this brief ironic poem by Roque Dalton:

Little Letter

Dear philosophers,

dear progressive sociologists,

dear social psychologists:

don't bother so much with alienation

here where the most fucked up thing

is the foreign nation. (Text and Photo: Cubadebate)